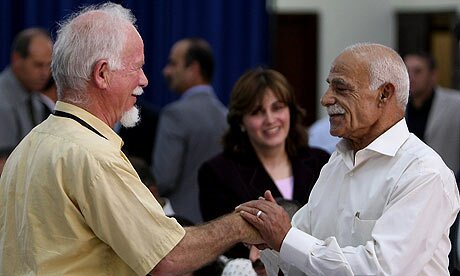

Uri Davis, left, at a Fatah meeting in Ramallah

By Peter Beaumont, The Observer – 23 Aug 2009

www.guardian.co.uk/world/2009/aug/23/uri-davis-interview-israel-fatah-palestine

Uri Davis is used to denunciations. A “traitor”, “scum”, “mentally unstable”: those are just some of the condemnations that have been posted in the Israeli blogosphere in recent days. As the first person of Jewish origin to be elected to the Revolutionary Council of the Palestinian Fatah movement, an organisation once dominated by Yasser Arafat, Davis has tapped a deep reserve of Israeli resentment. Some have even called for him to be deported.

He has been here before, not least as the man who first proposed the critique of Israel as an “apartheid state” in the late 1980s. Davis’s involvement in the first UN World Conference Against Racism in Durban in 2001 was condemned by the Anti-Defamation League. During a career of protest he has been described – inevitably – as a “self-hating Jew”. He calls himself an “anti-Zionist”. And his personal history is a fascinating testimony to the troubled history of the postwar Israeli left and forgotten trajectories in the story of Israel itself.

The man elected to the Revolutionary Council in 31st place from a field of 600 has been as much shaped by the tidal forces of recent Jewish history – not least his own family’s sufferings in the Holocaust – as any fellow citizen of Israel. But he disputes a largely manufactured account of that experience that he believes has been used deliberately “to camouflage” its “apartheid programme”. Now he enjoys an extraordinary mandate to explain his own views. And he hopes, too, that just as the small number of white members of the ANC widened its legitimacy during the apartheid era in South Africa, other Jews can be attracted to participate in Fatah, transforming it into a broader-based movement that stands for equal rights for both Arabs and Jews in a federated state.

So what does Davis believe, and why? His father was a British Jew who met his mother, a Czech, in British Mandatory Palestine in the mid-1930s, where they married in 1939, four years before his birth. While his mother escaped the transports to the gas chambers at Auschwitz, many in her family did not. It is a familiar story in Israel. But the lesson that Davis learnt from it was different from the vast majority of Jews who concluded that never again could Jews depend on others to guarantee their security from persecution.

“An important part of the education that I received from my parents,” Davis recalled last week, “was never to generalise. To beware of every sentence that begins with ‘all’. It was not ‘all’ Germans who killed my mother’s family. It was some Nazis.” Another distinction was emphasised by his mother. “If she heard the suggestion of vengeance, she would be horrified. She sought justice. One of the biggest problems addressing a Zionist audience is that the distinction between justice and vengeance has collapsed.”

He is 66 now, but that warning from his parents on the risk of demonising the Other still resonates in Davis’s language. He is insistent that generalities should be avoided, not least the “normative idea all Israelis are exposed to: that all Arabs hate the Jews and all Arabs want to drive the Jews into the sea”.

His own self-description is a case in point, fine-tuned over the decades. “It has gone through a number of stages. In my autobiography in the mid-1990s I described myself as a Palestinian Jew. That has now changed to a Palestinian Hebrew of Jewish origins.” How he frames his own identity is part of his attempt to impose an “alternative narrative” to the one that has dominated Israel since its foundation in 1948 by what he describes as “a settler-colonialist” strand of Zionism built on a massive act of “ethnic cleansing”. That moment – known as the “Nakba”, or the catastrophe to Arabs – saw the flight of 650,000-750,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled from their homes by Jewish forces.

Davis is careful with his definitions of both “Zionism” and his own “anti-Zionism”. The Zionism that he opposes is the “political Zionism” of Israel’s founders, the Zionism that amounts, he says, to land grab based on ethnic cleansing.

Davis himself insists on reclaiming a wider meaning for the word, not least because he was shaped, as he grew up, by a different school: the “spiritual Zionism” of thinkers such as Ahad Ha’am, religious philosopher Martin Buber and Judah Magnes, co-founder of Jerusalem’s Hebrew University.

In contrast to political Zionism, which saw Jewish statehood alone as a solution to the Jewish question, these spiritual Zionists believed Palestine could not accommodate a Jewish homeland but should become a national spiritual centre that would support and reinvigorate the Jewish diaspora.

Davis has written how his own “intellectual and moral development was profoundly influenced by Buber’s writings” although he has fiercely condemned Buber’s later actions, not least Buber’s appropriation of a house in Jerusalem belonging to the family of the late Palestinian activist and writer Edward Said.

Then there was Leon Roth, one of his father’s relatives and a fellow professor of Buber at the new Hebrew University. Roth resigned his post after witnessing the treatment of the Palestinian Arabs in the creation of Israel and returned to Cambridge.

But if these were formative influences on Davis, it is how he interpreted what he saw growing up in the young state of Israel that marked him out as different. Reading Gandhi and Martin Luther King led him to a pacifist position that saw him refuse military service in the 1960s, at a time when it was almost unheard of. He was eventually assigned to “alternative” service working on a kibbutz on the border with the Gaza Strip.

“I refused to participate in the armed patrols of the kibbutz fence on the border and that led to daily shouting matches. Then one of the members took me to the periphery of the kibbutz where there was a cluster of eucalyptus trees. He said: ‘What can you see?’ And I said trees. Then he took me into the wood and showed me a pile of stones. He asked me what I could see and I said: ‘A pile of stones.’ He said: ‘No. This is the [Arab] village of Dirma. Its residents are refugees while we cultivate their land. Now do you understand why they hate us and want to drive us into the sea?

“And I said, ‘But there is an alternative. We could invite them back and share it with them.'” He pauses. “If looks could kill. I saw that he saw me as a hopeless case. And I’m proud to say I’m still that hopeless case.”

Davis experienced a second moment of epiphany decades later during the first Gulf war, when Iraq was firing Scud missiles at Israel – a moment of insight related to an unresolved question from his childhood. “I was born in Jerusalem, but I grew up on a farm near Herziliya. I would walk with my peers down to the beach and pass the ruins of an Arab village under the shadow of a mosque that was still intact. And the dominant narrative deleted the reality. The elders of my community said they had pleaded with the elders of the Arab village to stay. And the elders of the Arab village refused. I had no way to challenge this for decades.

“During the first Gulf war the penny dropped. The mayor of Tel Aviv was abusing all those residents who had fled under the threat from Scuds. After the war ended, the families returned. They used their keys. Put their cash cards in the ATMs. Re-opened their shops. What was significant was that no one said to them: anyone who has left has lost their property rights. That was my second crossroads.”

Davis published Israel: An Apartheid State in 1987. He distinguishes between racism and apartheid, which, he argues, requires not simply an official value system that distinguishes on a racial basis but a legal reality. Indeed, Davis has written that it is wrong to single out Israel on the grounds that it is more racist than other states in the UN. Rather he believes it should be singled out because, as he wrote in a letter to Al-Ahram newspaper in 2003, “it applies the force of law to compel its citizens to make racial choices, first and foremost in all matters pertaining to access to land, housing and freedom of residence”.

Davis’s lifetime of dissent has not been without consequences. After joining Fatah, Davis began a long period of “de facto exile” at the suggestion of his lawyer to avoid a show trial. He taught during that time at a number of British universities, including Bradford, Exeter and Durham.

Returning to Israel and the Occupied Territories in the mid-1990s, following the Oslo Accords, Davis struggled for years to secure an appointment at an Israeli academic institution. ” I kept my affiliation with Exeter and Durham, which helped me with periodical research that they farmed out to me. I also had an inheritance.” It was only recently that he was appointed to teach a course at the Palestinian Al-Quds university on critical Israeli studies.

His marriage in 2008 to a Palestinian woman has not made life easier for him. She has been denied a permit to live in Israel, while Davis is forbidden by Israeli law to live in an area under Palestinian authority control as an Israeli citizen. In consequence, he is vague both about the circumstances of his conversion to Islam shortly before the wedding and where he now lives, describing those arrangements as “private”.

What does he hope to achieve as a Palestinian Hebrew who is a full member of the Revolutionary Council?

His core message, he explains, is “to suggest” to his new colleagues that there is nothing to fear in recognising the notion of a Jewish state. “The correct response is that we will not recognise an Israel defined by political Zionism.” And perhaps just as importantly, Davis believes that Fatah can expand its role from representing only Palestinian Arabs to representing all of those who oppose “settler-colonialism”.

“It cannot win the struggle for equality that it has waged for so long as long as it remains only representative of Palestinians. To win the moral [high ground] it has to project itself as a democratic alternative for all. That is the message I first delivered and that I have persevered with and has led to my election to the Revolutionary Council after 25 years.” It seems unlikely that condemnations on Israeli websites will prevent Uri Davis from giving up on his unique mission now.