By Stephen R. Shalom

Logos: a journal of modern society & culture

vol. 12, no 3 (Fall 2013)

http://logosjournal.com/2014/shalom/

Stephen R. Shalom

The issue of one state or two states has been very divisive among leftist supporters of justice for Palestinians. It will of course be up to Palestinians themselves to decide the terms on which they will settle their long-standing conflict with Israel.1 But outsiders can offer their assessments and analysis, particularly as the debate has important implications for their Palestine solidarity work, and may be of benefit as well to Palestinians. I will begin by explaining a general approach to political questions of this sort. I will then turn to the Israel-Palestine conflict and consider how we might apply this general approach to that conflict. I will then try to answer two questions: whether a two-state settlement moves us forward on the path of justice and whether its prospects for realization are significantly greater than the one-state alternative. Next I will address the question of whether there are moral arguments that require us to reject any two-state settlement. And finally, I will discuss the political implications of this debate.

Assessing Political Campaigns

Let me begin with an analogy that I hope will illuminate a way to approach these kinds of political questions. Consider the example of the living wage campaigns that are being pursued around the country, demanding that low-paid workers receive enough to provide for their basic needs. Typically these campaigns, supported by leftists, call for local ordinances or policies that set some minimum compensation level, well above the existing minimum wage, for all employees. Now imagine if a labor solidarity activist opposed the living wage campaign, arguing that “The problem is with capitalism and the whole wage system, not the low wages paid by some employers.”

I assume we would reply, “Yes, the problem is capitalism, but we’re not going to be able to solve that overnight. People who are hungry today can’t afford to wait until we have brought capitalism down. Unlike total system transformation, a living wage can be won in the near term — not that we will win, but we can win in the near term; ending capitalism, on the other hand, we have no chance of winning for many years. A victory in a living wage campaign would do two things: first, it would provide an immediate improvement in the lives of people who are suffering; and, second, it would show people that change is possible and that there is an alternative to hopeless resignation.” Yes, there are limits to what can be accomplished under capitalism, contrary to the claims of liberal critics of the status quo — and we should always make these limits clear while we participate in struggles to achieve reforms. But it would be thoroughly wrongheaded to refuse to support a living wage campaign in the United States today because it’s not perfectly just or to denounce those who support it as engaged in morally unacceptable behavior. And it would be especially inappropriate for those of us who are not low-paid workers to tell low-paid workers not to accept $15 an hour because they ought to hold out for the end of capitalism.

The same logic holds even if one doesn’t support socialism. That is, imagine another hypothetical critic of living wage campaigns who says $15 an hour is a morally repugnant wage and nothing less than $25 per hour ought to be accepted. I assume we would reply, “Yes, merely guaranteeing everyone a living wage is unjust, as indeed any improvement in anyone’s life situation that falls short of our ideal of justice, whatever that happens to be, will be unjust. But our refraining from achieving reforms while we wish for a perfectly just outcome doesn’t bring that outcome any closer. On the other hand, a living wage campaign both improves people’s lives, which is important, and can give the workers and their supporters the sort of victory that helps build a movement that can push for further improvements.” The same logic holds as well for all sorts of political campaigns. On the environment, on women’s rights, and on a whole host of other issues we will often support efforts to achieve some reform that is less than our ideal. We do this because we realize that we can’t yet win our maximum demands, but we want to improve things in the meantime, while building movements that can achieve more.

This doesn’t mean that it’s always right to go for limited reforms. One needs to make a serious judgment about what’s possible under the particular circumstances prevailing at each time and place. So in 1968, for example, it was right to criticize the Communist-led unions in France for being bought off by some moderate improvements when the whole capitalist system might have been successfully challenged. Sometimes transformative change is possible. But when your considered judgment tells you that the best you can do is win $15 an hour, then one needs to support that campaign and not refrain from doing so because it falls short of one’s ideal. Does thinking about what seems achievable or realistic make one a counterrevolutionary naysayer? Shouldn’t leftists have faith in people’s potential to change the world? Gramsci’s advice is relevant here: we want to have optimism of the will, but pessimism of the intellect. We believe in people’s abilities to rise above their circumstances and fight to create a better world. But we’d be crazy to lay siege to the White House tomorrow because we think it’s possible that 100 million Americans will rise up and support us. We welcome and hope for unexpected inspirational moments; we don’t count on them.

Framing the Palestine-Israel Conflict

Let me turn now to the Palestine-Israel conflict. There are countless controversies involved in this conflict that I cannot take up here, so I will simply state the following as assumptions that underlie my arguments below:

- Israel committed a great crime against the Palestinian people in 1948;

- The Palestinian refugees have a right of return, as recognized by international human rights organizations2;

- Israel is a highly discriminatory society, not just towards those it holds under occupation, but towards its Palestinian minority.

It is therefore true that any settlement that ends the Occupation but that doesn’t address the crimes of 1948 or the systemic discrimination within Israel’s pre-1967 borders will be unjust. But there are many other injustices — among them: religious intolerance, the oppression of women, and the horrendous discrimination against Palestinians in Lebanon. And it will therefore also be true that any settlement that “only” ends the Occupation, ends discrimination against Palestinians in Israel, and implements the right of return will also be unjust. Moreover, any settlement that takes as a given the borders imposed by the colonial powers following World War I will also be unjust, in particular any settlement that is based on the borders of Palestine that existed only from 1923 to 1948. And, as any leftist will surely agree, any settlement that retains capitalism will also be unjust. So the question isn’t whether a two-state settlement is unjust in this pure sense. Of course it is. The question is whether a two-state settlement can be an intermediate step along the path to justice. A second question is whether a two-state settlement is significantly more attainable than some other settlement that is more just. If step two is just a little bit more difficult to achieve than step one, then we can easily skip the first step. But if the gap between step one and two is large — if the time frames for their realization are substantially different given the prevailing balance of forces — then the first step will be a sensible way station to the top of the staircase. Before turning to these questions, however, let me clarify that I am considering here a real two-state settlement, not a settlement that is called “two state” but is actually some variation of Bantustans. In a real two-state settlement, the borders are essentially the 1967 borders, East Jerusalem is the capital of the Palestinian state, the settlers are gone, there is no Israeli military force controlling the Jordanian border or the Gaza coast or Palestinian airspace. There are other two-state settlements — those put forward by many Israeli and U.S. politicians — that bear no relation to the idea of two sovereign, viable states in Palestine. But the fact that Netanyahu, for example, supports a totally insincere and repugnant arrangement that he calls a two-state settlement no more discredits a real two-state settlement than the existence of some repugnant one-state arrangements advocated by several Israeli rightwing politicians and settler leaders3 or by Islamic fundamentalists discredits all one-state settlements. If one wants to challenge a two-state settlement on principle, then one has to direct one’s criticisms at a real two-state, not a bogus two-state settlement.4

A Step on the Path to Justice?

So does such a two-state settlement further the cause of justice? Does it improve people’s lives in such a way that it is a step on the path to justice? The most obvious consequence of a two-state settlement is that it would end the Occupation. This would be an immense human benefit to the people of Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem. There would no longer be the horrendous suffering in Gaza, the world’s largest open air prison camp, where travel, most imports, and almost all exports are blocked, and where access to the coast is restricted. Palestinians in the West Bank would no longer have to navigate countless roadblocks, checkpoints, and Israeli-only roads. Their houses would no longer be demolished nor their lands seized. Their aquifers would not be raided so that Jewish settlers could fill their pools, while Palestinians receive only two thirds of their minimum needs. And Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza would have self-determination and the right to vote for their own sovereign government.

A two-state settlement certainly does not resolve the refugee problem. But even if a two-state settlement resulted in not a single Palestinian being allowed to exercise his or her right of return to Israel, an independent Palestinian state would offer a destination for some of the most downtrodden of the Palestinians, those living in the refugee camps of Lebanon.5 To be sure, someone driven from their home in Lydda (inside the Green Line) has not received justice by being allowed to move to, say, Tulkarm in the West Bank. Nevertheless, there may well be many refugees, especially those living under severe discrimination in Lebanon, who would choose to move to this Palestinian state, and who would be better off for so doing.6 This doesn’t achieve justice for the refugees, or fulfill their right of return, but it might improve the lives of those worst off.7 A two-state settlement would not do much directly to better the situation of the Palestinians of Israel. However, the political struggle for equality within Israel would likely benefit from the reduction in tensions to which a two-state settlement would presumably lead.8 In general, repression of Israel’s Palestinian minority has tended to be greatest when national security tensions have been highest. For example, the largest killing of unarmed Palestinian Israelis in many years took place in October 2000 as the second intifada was getting under way in the territories9; the rights of elected Palestinian Israeli legislator Haneen Zoabi were challenged because of her support for efforts to break the siege of Gaza.10

Undeniably, discrimination against Israeli Palestinians is deeply entrenched and not simply a function of the Occupation. But as in many countries, it is easier to squash internal dissent during times of national danger. Israeli Jewish dissidents too are likely to fare better when they can’t be smeared as allied to foreign enemies. A two-state settlement would further the cause of justice in one other way. I assume that a real two-state settlement can only come about as a result of a mass popular non-violent mobilization of Palestinians, with a secondary role played by sympathetic boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) actions outside. But if these actions resulted in a two-state settlement, it would be a tremendous victory for grassroots struggle that would strengthen justice movements going forward, leading to further gains, improving the situation of refugees and Palestinians in Israel.

Likelihood of Success: The Correlation of Forces

But even if a two-state settlement would be a step on the road to justice, a second question needs to be addressed: whether there is some more just settlement that is not much more difficult to achieve than the two-state settlement. I think any careful assessment of the matter will conclude that as difficult as it will be to achieve a decent two-state settlement, a one-state settlement would be exponentially more difficult. One way to judge this is to look at what is sometimes called the correlation of forces: who supports a position and who doesn’t.

- A two-state settlement represents an international consensus. Some say this international consensus is a myth,11 that no one cares two figs about two states. Maybe it’s true that the overwhelming endorsement that two states gets in UN votes is a cover for a distinct lack of enthusiasm, but if so it’s still got far more international backing than any one-state arrangement. Annual UN General Assembly votes in favor of a two-state settlement have been overwhelming; the few dissenters have voted no not because they favor a single democratic state in Palestine, but because they want to maintain Israeli hegemony over the whole of Palestine.

- A two-state settlement has the support of international law, as reflected in the 2004 Wall decision of the International Court of Justice and in numerous UN resolutions. There is nothing about Israel’s existence within its pre-1967 borders that runs afoul of international law. It is of course true that Israel stands in violation of international law in many respects, but its pre-1967 border (apart from Jerusalem) is not one of those violations.12 I don’t think law is sacrosanct — it often reflects the interests of the rich and powerful — but for better or worse it’s easier to win a demand backed by international law than one that is not.

- No significant Palestinian political party has adopted the goal of one democratic state. Not Fatah, not Hamas, the only two parties with a mass following.13

- To be sure, these are both corrupt parties and many Palestinians are fed up with them both. Nevertheless, their opposition to one state makes that option less achievable. Perhaps the single most popular politician in Palestine is the imprisoned Marwan Barghouti. Polls show that he would win any presidential election in the occupied territories.14 He supports a two-state settlement.15 A small group that included some former senior Fatah officials recently issued a declaration favoring one state,16 but their numbers are quite limited.

- Most Israelis and most Palestinians do not support a one-state settlement. One might be inclined to ignore Israeli opinion on the matter, given Israel’s colonial and oppressor role, but in terms of what can be achieved in the near term, the fact that while Israeli Jews oppose both one state and two states, they oppose the former far more strongly than the latter — while not morally relevant — is politically relevant. Consider again the living wage analogy. What makes a living wage campaign a more winnable and hence practical political demand than, say, a $25 minimum wage campaign is not the opinion of low-paid workers. Of course they would be thrilled to have $25 an hour. But a realistic assessment of the odds of success tells us that the opposition of employers to paying $25 an hour will be much greater than to paying $15, so much so that the $25 demand has virtually no chance of realization in the near term. Does this mean that we attach moral value to the views of employers? No. In a good world, the exploitation of labor wouldn’t exist at all. But we’re not in a good world, and in the world we do live in the extent of capitalist opposition constrains what we can achieve.

What about Palestinian opinion? Here, we need first to clarify which Palestinians we are talking about. There are Palestinians in the occupied territories, Palestinians who are citizens of Israel, Palestinian refugees living in Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan (some of the latter with Jordanian citizenship), and other Palestinians dispersed throughout the world. Which of these are entitled to a voice in settling the Israel-Palestine conflict? On the question of the rights of refugees, all the Palestinians dispossessed by the conflict are entitled to a say. As a matter of basic democratic principles, the subset of Palestinians living under occupation cannot make a deal at the expense of the refugee rights of other Palestinians. On the other hand, those who do live under occupation are entitled to make whatever arrangement they choose to end that Occupation, without needing the concurrence of those who are not living under the Occupation. Thus, in theory a settlement could come in separate parts: an end to the Occupation might be signed by those under occupation, with a resolution of the refugee question awaiting terms acceptable to all who have been dispossessed.17 Israel, however, would likely refuse to accept any settlement that didn’t “end” the conflict. But perhaps it would be possible to separate the issues — ending the Occupation and keeping the other issues open by means of a hudna, the long-term truce advocated by Hamas. In 2011, Mahmud Abbas, head of the Palestinian Authority, stated that in the event of a peace agreement “we will have a referendum involving all Palestinians on all final status issues, but if one of the countries hosting refugees refuses, the referendum cannot be held.”18

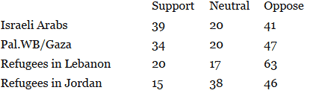

More recently he has spoken of a referendum, but it is unclear whether he means to be including the Palestinians not under occupation.19 Potential differences of opinion between various groups of Palestinians may, however, not matter much in practice. Many polls have confirmed that Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza reject a one-state settlement.20 But in addition, as best we can tell from the polling data, no group of Palestinians — those in the occupied territories, those who are Israel citizens, or those in Lebanon or Jordan — favors a one-state settlement.21 When asked whether they support the pre-1967 border “being used to define the boundaries between Israel and a future Palestinian state,” three quarters of Israeli Arabs answer in the affirmative as do a plurality of Palestinians in the occupied territories and refugees in Jordan. Lebanon refugees say they reject this option, but when asked whether it is important to them that there be a Palestinian state located in “all of the West Bank and Gaza,” with a capital in Jerusalem, 77 percent of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon answer yes.22 Thus, as difficult as a two-state settlement will be to achieve, it has more support than a one-state settlement does from all groups of Palestinians, from Israelis, from Palestinian parties, from international law, and from world governments.

Now obviously opinions can change, and part of what influences opinions are grassroots solidarity movements. Some suggest that the same way that grassroots boycott, divestment, and sanctions pressure brought down apartheid in South Africa, so too can it force the creation of a single state in Palestine. But it is important to realize the very different international standing of South African apartheid and Israel’s crimes of 1948. In Britain, South Africa’s main foreign backer, a boycott of South Africa was endorsed by the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress in 1959 — 35 five years before apartheid fell.23 A British poll shortly after the Sharpville massacre in 1960 showed 80 percent opposed apartheid.24 The United Nations condemned apartheid as early as 195025 and in 1977 the UN Security Council unanimously enacted a mandatory arms embargo against South Africa.26 In 1986, the U.S. Congress overrode Reagan’s veto to pass a comprehensive set of sanctions against South Africa.27 Public opinion in the United States was so strongly hostile to apartheid that even Reagan was compelled to declare: “America—and that means all of us—opposes apartheid, a malevolent and archaic system totally alien to our ideals.”28 Eight years later, the first democratic elections were held in South Africa. Contrast that with the international response to Israeli policy. There is widespread condemnation of the Israeli Occupation. But it is hardly the case that “all of us” — in the United States or even in Europe or most of the Third World — oppose the Zionist actions of 1948. If asked, most people would have no idea what we were talking about. There have been some important successes of the BDS movement, but almost all of these that involved significant organizations have focused on the Occupation and not on the 1948 issues.29 If the Palestinians in the occupied territories were able to mobilize a mass-based popular movement that gained broad international sympathy, external support in the form of BDS could put significant pressure on Israel to give up its occupation. But for BDS to have an appreciable impact on the 1948 issues in the foreseeable future seems implausible.

The Likelihood of Success: Political and Economic Realities

Several other arguments have been advanced as to why a two-state settlement is difficult if not impossible to achieve. Each one of these arguments, however, seems to apply with greater force to the possibility of realizing a one-state settlement.

- Zionism, it is argued, is a racist ideology driving a program of expansion and oppression, and unless this ideology is defeated, expansion and oppression will continue. Certainly Zionism as understood by most Israelis today is racist. But a one-state settlement requires as a precondition the defeat of Zionism, which means we will have no improvement in the lives of Palestinians until Zionism is smashed. A two-state settlement, on the other hand, would over time and under conditions of peace allow ties of inter-ethnic solidarity to be established, undermining the hold of racist ideology, without needing to postpone all improvements until that happy day when Zionism is defeated.30

- It is said that the Zionist Israeli state will resist being confined to 78 percent of Palestine. This is true, but it will resist even more being confined to 0 percent. In general, it’s harder to get oppressors to give up more than to give up less. In neither case do they do this out of the kindness of their hearts. They do it because we’ve applied pressure; we’ve raised the costs of their continuing to oppress. It will take more pressure, more raising of costs (and surely more bearing of costs by those on the side of justice) to get them to concede more than to concede less.

- Many of the leading Israeli corporations — whether located within the Green Line or not — benefit economically from their domination of the territories. True enough.31 But these corporations benefit even more from their domination of Israel within the pre-1967 borders. They will hate to give up the former, but they will hate giving up the latter even more.

- The Zionist project benefits from exploiting the water and other resources of the West Bank. But again, it will surely be easier to get them to concede some of the resources of greater Israel than to concede Israel entirely.32

- The IDF gets all kinds of strategic benefits from controlling the West Bank and will be loath to give that up. But a one state will not just mean giving up these benefits, but will risk turning over the entire IDF (and its nuclear weapons) to a Palestinian majority.

- It is often noted that the settlers are a powerful voting bloc, with influential cabinet ministers among their number. Again, this is true, but the Israelis who support a Jewish state are an even more powerful voting bloc (approaching 100% of the Jewish population), and these Israelis count every cabinet minister among their number.

Another argument against the possibility of a two-state settlement is that a Palestinian state restricted to 22 percent of the area of mandate Palestine, divided into two parts to boot, is simply not viable economically. An independent Palestine would indeed be small, though larger than 31 other UN member states. Its population density would be among the highest in the world, surpassed only by Monaco, Singapore, Bahrain, Malta, Bermuda, the Maldives, and, Bangladesh, and that’s without factoring in any refugees who might “return.” Palestine would have a number of valuable economic assets — some offshore gas, important tourist sites, a potential port in Gaza, and considerable human capital. But it is evident that in the short run Palestine would need substantial capital from outside.33 Some of this would come from the compensation paid to refugees and some from international donors.34 There is no doubt that the economy of a Palestinian state would be greatly aided by integrating with neighboring states, and certainly this is something one would hope would be pursued once there are conditions of peace. The difficult economic situation that would be faced by an independent Palestinian state, however, has troubling implications for a one-state settlement as well. If Palestinians can’t thrive in their own state, how are they going to avoid domination in a single state? Consider the example of South Africa. “One person-one vote” was achieved in a country with a large black majority.

Nevertheless, the small white minority had been able to use its economic clout to maintain its position of privilege in one of the most unequal societies in the world. We don’t know what percentage of the population of a single state in Palestine would be Jewish, but even with a large refugee influx, the Jewish proportion of the population would be far greater than the white proportion in South Africa. And the existing economic and educational disparities between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs would grow as impoverished refugees from Lebanon returned. Universal suffrage has not generally been able to prevent rich minorities from dominating their societies and there is no reason to expect a single state in Palestine to be an exception.35 The most commonly-heard argument against the possibility of two states is that the settlements, the settler-only roads, and all sorts of infrastructure that crosses the pre-1967 border have basically already created a single state. The two sides of the Green Line have increasingly become interdependent. One state, it is said, is a fait accompli and all that can be done now is to fight to convert that oppressive Zionist one state into a just one state. What the Zionists call creating facts on the ground has certainly been the intent of Israeli policy in the occupied territories. The settlements and roads have been located precisely so as to turn the West Bank into a series of disconnected Bantustans, with population centers cut off from each other, with villagers cut off from their agricultural fields, and with a majority of Palestinians cut off from Jerusalem. But these facts on the ground are not as irreversible as claimed. There are two kinds of facts on the ground: infrastructural and human. The infrastructural are the easiest to deal with. The housing units of the settlements are not an obstacle to two states at all: emptied of the settlers, these units could provide some of the necessary housing for those who have languished in refugee camps. The Wall, of course, would be torn down, as it would be under a one-state settlement and as the Berlin Wall was torn down. The Israeli-only roads would become roads for all the people of the Palestinian state, and where the roads divide villages from their lands, intersecting roads can be built. The human facts — the settlers themselves who moved to the occupied territories in violation of international law — can move back behind the Green Line.36

For those settlers who live very close to the border, Palestinian negotiators can decide whether they want to trade small bits of land for comparable land elsewhere. In addition, the Palestinians could allow Israelis to live as foreign residents in Palestine (under the laws of the Palestinian state, but of course without the IDF) or even to apply for Palestinian citizenship. But they are certainly not entitled to their ill-gotten settlements. Oddly, in their effort to show that a two-state arrangement is no longer viable, some one-state advocates are prepared to allow the settlers to remain in their illegally-acquired settlements.37 This strikes me as a morally problematic position,38 and one unlikely to receive much support from Palestinians under occupation. It is the logical consequence, however, of the claim that the settlements make a two-state outcome impossible: for if it’s the supposed inability to move the settlers that makes a two-state outcome impossible, then how can they be moved under the one-state alternative?

Should the two-state settlement be rejected as immoral?

I want to turn now from the objections to the two-state settlement that claim it is unachievable to those that claim that it is morally and politically unacceptable. The first of these arguments is that a two-state settlement betrays the Palestinian right of return. Note first, however, that from a logical point of view the two questions (one state or two states and the right of return) are quite distinct. One can have a right of return whether there are two states or one state in Palestine. After all, UN General Assembly resolution 194, which first enshrined the Palestinian right of return in December 1948, called for the refugees to be permitted to return to Israel in its pre-1967 borders: that is, to the territory of what would be Israel under a two-state settlement.39 Now, in fact, I think the likelihood of the right of return being fully implemented in the foreseeable future in either a one-state or a two-state version is very close to zero. This low probability doesn’t make the right of return unjust. But it does make it extremely ill-advised for outsiders to encourage Palestinians to refuse any settlement because if they simply hold out a little longer, they will achieve all they deserve. This would be like urging U.S. workers on strike under present conditions to refuse to settle until the boss agrees to make them co-owners.

Among these two near zero probabilities, I would argue that paradoxically a full right of return is easier to implement in a two-state than a one-state settlement. Why? Because in a two-state settlement with the right of return Jews would remain a majority (since the Palestinians originally from the areas that became the Palestinian state and their descendants would not be part of Israel), while in a one-state settlement with the right of return Jews would more likely be a minority. Therefore, Israeli resistance to the former is likely to be much more intense than to the latter.40 Let me be clear: I believe that Israeli Jews are entitled to national rights,41 but this doesn’t mean they have a right to a separate state; national rights can be realized in some sort of binational state.42 So if there were a binational state, there would in principle be no moral reason why there needed to be a Jewish majority. What matters in practice, however, is that an overwhelming majority of Israelis is unalterably opposed to both a full implementation of the right of return and to losing its Jewish majority. Winning two near impossibilities is even more unlikely than winning one.43 A more general moral objection to the two-state settlement is that we ought to be opposed on principle to ethnocentric states. A two-state settlement means a Jewish state and Palestinian state — two ethnocentric states — and this should be unacceptable to leftists. On one level this argument is indisputable: leftists reject ethnocentrism.44 But they reject as well capitalism and patriarchy and many other evils, and we don’t accuse those who call for a democratic secular state of thereby supporting capitalism and patriarchy because a democratic secular state is less than a democratic, secular, anti-capitalist, non-patriarchal state. One state supporters would correctly reply to such a charge that the establishment of one state does not mean the end of political contestation; the struggle against capitalism and patriarchy would continue and would likely not lead to victory until long after the attainment of the single state; but it would be foolish to delay solving the problem of national suffering in Palestine until our ideal society was achieved. And the same logic applies to the two-state settlement. To accept a two-state settlement because of the benefits it would bring to long-suffering people does not mean that one endorses the evils that this limited reform would not address.

On the contrary, it will be essential that vigorous struggle against the ethnocentric character of Israel continue after any two-state settlement. It should be noted that the left has many times called for solving some national conflict with the establishment of separate states. The East Timorese were offered a one-state option by the Indonesians (autonomy within the Indonesian state) and they rejected it in a referendum, without incurring leftist criticism. If Puerto Ricans demanded independence, what leftist would demur? If Kashmiris called for a separate state (rather than being part of either India or Pakistan) would they be accused of supporting ethnocentrism? Obviously, each one of these cases has its own particular circumstances, but the point is that it is not a fundamental left principle that separate states are always reactionary. In 1947, the partition of Palestine was unjust. The rights of the Jews in Palestine could have been accommodated by a binational state,45 while the partition plan, which granted 55 percent of the territory to a third of the population that owned less than 10% of the land, was unfair to the Palestinian majority, particularly to the large Palestinian minority that would find itself within the boundaries of the Jewish state46 — even apart from the ethnic cleansing that followed. But 65 years of war have now passed and both communities want their own separate state. Partition in 1947 was imposed against the wishes of the majority community in Palestine; a single state today is widely opposed by both communities. A binational state would, in my view, be morally preferable to two states, but it requires a degree of popular support and mutual goodwill that are many years off.

The One-State/Two-State Debate and the Palestine Solidarity Movement

Palestinians will have to make their own decision on what they are willing to accept. If they decide that they are unwilling to accept anything less than the full right of return to a single state stretching from the Mediterranean to the Jordan, that is their choice. Personally, I think this would be a mistake, given what I think are the negligible prospects for achieving this goal in the foreseeable future, but it is their call. The converse is also true. If, given the prevailing circumstances, Palestinians opt to accept, however reluctantly, something less than this goal, it is inappropriate for solidarity activists to denounce them as collaborators or sell-outs. What members of the solidarity movement owe Palestinians, first and foremost, is to offer their honest assessment of what they think activists can achieve by their advocacy work in their home countries. To the extent that a Palestinian decision on what to accept in any settlement is based on an understanding of the amount of pressure that can be mobilized on their behalf in the West, Palestinians need to have accurate information on the political dynamics of the United States or other Western societies, information that they can’t readily get in the occupied territories or the Lebanese refugee camps.

We do the Palestinian cause no good if we exaggerate their chances of achieving their maximalist goal. We do them no good if we try to stifle pessimistic prognoses by accusing those who offer them of being insufficiently radical or of not really being in solidarity with the Palestinian cause.47 I think it’s possible to build significant support in Europe for sanctions against Israel for its occupation policies — and succeed in getting such sanctions implemented. I don’t think, however, that it will be possible for a very long time to build significant support in Europe for sanctions against Israel for its failure to redress its crimes of 1948 — let alone get them implemented. In the United States, where Israel’s political clout is stronger, I believe we can build a movement challenging Washington’s ability to give a blank check to the Occupation. But I don’t think we have the slightest chance in the foreseeable future of getting Washington to press Israel to accept a one-state settlement. It took three and a half decades from the first boycotts of South Africa to apartheid’s collapse, even though the apartheid regime faced a movement capable of imposing much heavier costs — because of South Africa’s dependence on black labor — than Palestinians can impose on Israel. Do one-state advocates think it will take less time to get Israelis to surrender?48 If so, they need to explain what justifies their optimism?49 If not, they need to honestly address what happens in the meantime. Negotiators for the Palestinian Authority have sometimes used the one-state “threat” as a tactic for getting the Israelis to be less resistant to a two-state settlement.50 This tactic, however, carries the risk of creating a counter-productive backlash among Israelis. While it might push them to accept a decent two-state settlement, it might also lead them to back more rightwing forces.51

It is indeed the case that some want to focus on a two-state settlement precisely because they don’t want to have to address the Nakba or the discriminatory nature of Israeli society. Against these folks it is important to speak the truth. But others reject one-state advocacy within the solidarity movement not only because Palestinians will have to make their own decision, but also because they believe that a two-state settlement is the best that can be achieved at this point in time. They do not try to hide the crimes of 1948 or the systemic oppression of Israel’s Arab population; indeed, many of them have long been involved in exposing and fighting against these injustices. Nevertheless, their honest assessment of the political realities is that while a two-state settlement is marginally possible in the near term, neither a one-state settlement nor a full realization of the right of return is achievable for many years to come. These “two-staters” share much common ground with “one-staters” and there should be many opportunities for cooperation. In particular, both groups appreciate the suffering of the Palestinian people, denounce the horrendous (and worsening status quo), and want to maximize outside pressure on Israel to force it to reverse that status quo. Both reject the various Bantustan-like and non-viable states that are being promoted by many Israeli and U.S. politicians. Both groups oppose an outcome that gives the Palestinians — in Yitzhak Rabin’s words — “an entity which is less than a state.”52 Some things are harmful to both the one-state and two-state causes. Occasionally, a one-state advocate will cheer the defeat of some step toward a two-state settlement (e.g., “I am just so pleased that Netanyahu has placed impossible conditions in front of the ‘two-state solution.’ Go Bibi!”53).

This may be facetious, but almost anything that makes a two-state settlement less likely means a strengthening of rightwing forces that will make a one-state outcome less likely as well.54 Sometimes a “two-stater” will criticize a “one-stater” for speaking the truth about past crimes that cannot be immediately redressed. But just as radicals should never refrain from expressing the limits of liberal reforms, even while welcoming them, so too members of Palestine support groups should not be discouraged from indicating the limits of ending the Occupation. This will help us avoid problematic tactics such as the one suggested by Peter Beinart.55 Beinart proposes that peace advocates should pursue a two-pronged approach: boycott settlement products while affirmatively purchasing products from within the Green Line to show our support for Israel within its pre-1967 borders. I agree with Beinart that boycotts focused on the Occupation make strategic sense, but to affirmatively buy Israeli products teaches the wrong lessons: it covers up the crimes of the pre-1967 Israeli state, it obscures the ongoing discriminatory treatment of Israel’s Palestinian citizens, and it even occludes the fact that the Occupation is controlled not from the settlements, but from within the Green Line.

In the same way, we wouldn’t have considered urging people to buy Indonesian products while it held East Timor, even if those products were produced in Jakarta. Other things being equal, a single state that accommodated the national rights of both Palestinians and Israeli Jews would be morally much preferable to a two-state arrangement. But if the prospects for a single state in the near term are remote and if the two-state settlement can bring some improvement to people who have been suffering for so long, then the two-state settlement ought not to be disparaged. Its achievement surely wouldn’t be the end of the story. Under conditions of peace, struggles can grow to democratize the highly discriminatory Israeli state and the Palestinian state, and cross-border alliances can be built aiming toward much more just outcomes, maybe going through the bi-national one-state option,56 maybe one day involving a socialist federation in the Middle East, and maybe well in the future the abolition of national boundaries altogether.

Stephen R. Shalom teaches political science at William Paterson University in New Jersey. He is on the board of New Politics and a member of the IOA Advisory Board.

Notes

- This article is an expanded version of a presentation made at the Left Forum, June 9, 2013. I would like to thank Bashir Abu-Manneh, Barry Finger, Glen Pine, Adaner Usmani, and the editor of the Israeli Occupation Archive, for their helpful comments. None of them is responsible for my conclusions or errors. ↩

- Amnesty International, “Israel and the Occupied Territories/Palestinian Authority: The right to return: The case of the Palestinians,” www.amnesty.org/en/library/asset/MDE15/013/2001/en/364a3000-db6e-11dd-af3c-1fd4bb8cf58e/mde150132001en.html (accessed 7/19/2013); Human Rights Watch, “Israel, Palestinian Leaders Should Guarantee Right of Return as Part of Comprehensive Refugee Solution,” Dec. 22, 2000, www.hrw.org/news/2000/12/21/israel-palestinian-leaders-should-guarantee-right-return-part-comprehensive-refugee-. See also the internal HRW documents posted by Norman Finkelstein, at http://normanfinkelstein.com/2013/there-is-in-history-no-right-of-return/. ↩

- E.g., Moshe Arens, “Is there another option?” Haaretz, June 2, 2010, www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/is-there-another-option-1.293670. ↩

- As Michael Neumann puts it, “calling something a two-state solution doesn’t make it one. It’s only a two-state solution if it results in two states, in the normal sense of two sovereign entities.” “The One State Illusion: Reply to My Critics,” Counterpunch, March 14, 2008, www.counterpunch.org/2008/03/14/the-one-state-illusion-reply-to-my-critics/. ↩

- On the condition of Palestinians in Lebanon, see Dalal Yassine, “Unwelcome Guests: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon,” Al-Shabaka Policy Brief, July 2010, http://al-shabaka.org/policy-brief/refugee-issues/unwelcome-guests-palestinian-refugees-lebanon. ↩

- So, for example, while 88 percent of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon said it was important that they be allowed to return to their original home, town, or village, 68 percent said that if this was not possible, then it was important that they be able to live in a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. (This latter figure represented a sharp increase from 2005, when it was 35 percent.) For Lebanese refugees, 77 percent say they believe a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza is important, and 68 percent are hopeful that they might live in that state. For refugees in Jordan, 97 percent want to be able to return to their original home, town, or village, and 96 percent want to live in a West Bank-Gaza Palestinian state. And for Palestinians living in the territories, the figures were 92 percent and 83 percent respectively. See James Zogby, Is Peace Possible?: A report on a comprehensive survey of attitudes among Israeli Jews, Israeli Arabs, Palestinians in the Occupied Lands, Refugees in Lebanon, Refugees in Jordan, and Jewish Americans, Zogby Research Services, October 2012, www.aaiusa.org/reports/

is-peace-possible, pp. 24, 26. ↩ - Moreover, the existence of a Palestinian state would benefit those Lebanon refugees who choose to remain in Lebanon. This is because in Lebanon “Palestinian refugees are subject to the legal regulations governing foreign workers, including the principle of reciprocity and the requirement to obtain a work permit. As there is no state of Palestine with official diplomatic relations and reciprocity agreements with Lebanon, this immediately creates an obstacle that prevents Palestinian refugees from obtaining work permits, especially within professional associations.” (Dalal Yassine, “Unwelcome Guests: Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon,” Al-Shabaka Policy Brief, 5 July 2010 {note removed}, http://al-shabaka.org/policy-brief/refugee-issues/unwelcome-guests-palestinian-refugees-lebanon.) Palestinians refugees from Syria now suffer from statelessness as well. See Rosemary Sayigh, “The Price of Statelessness: Palestinian Refugees from Syria,” Al-Shabaka Commentary, May 2013, http://al-shabaka.org/sites/default/files/Sayigh…En_May_2013.pdf. ↩

- In 2009 and 2010 in response to the question “If peace prevails between Israel and Palestinians through an establishment of Palestinian state at peace with Israel, which is more likely about the status of Arab citizens of Israel,” a plurality of Israeli Palestinians chose the option “rights will improve.” Shibley Telhami, “Israeli Arab/Palestinian Public Opinion Survey,” Saban Center for Middle East Policy, 2010, www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/…/reports/2010/12/09%20israel%20public%20opinion%20telhami/israeli_arab_powerpoint.pdf, slide 35. ↩

- See the Official Summation of the Or Commission Report, Sept. 2, 2003, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/…/…/OrCommissionReport.html. ↩

- Harriet Sherwood, “Israeli-Arab politician who was on Gaza protest flotilla can stand for re-election,” The Guardian, Dec. 30, 2012, www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/dec/30/israeli-arab-flotilla-election. ↩

- Kathleen Christison, “The Myth of International Consensus,” Counterpunch, January 24, 2008, www.counterpunch.org/2008/01/24/the-myth-of-international-consensus/. ↩

- On Jerusalem, see UN General Assembly Resolution 303, 9 Dec. 1949. This doesn’t mean that the expansion of Israel’s borders beyond those of the UN partition plan was just, only that no UN resolution or ruling by the International Court of Justice has ordered Israel to return to the partition plan borders. ↩

- Palestine Center for Policy and Survey Research, Poll No. 48, 13-15 June 2013, www.pcpsr.org/survey/polls/2013/p48e.pdf, p. 10 (question 20), p. 19, question 58. ↩

- Ibid., p. 10 (questions 17 and 18). ↩

- Adnan Abu Amer, “Time for Bold US Mideast Move – Marwan Barghouti,” Al-Monitor Palestine Pulse, May 28, 2013, www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/05/marwan-barghouti-fatah-palestine.html. ↩

- Amira Hass, “Senior Fatah officials call for single democratic state, not two-state solution,” Haaretz, May 17, 2013, www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/senior-fatah-officials-call-for-single-democratic-state-not-two-state-solution.premium-1.524443. ↩

- This is the conclusion that Noam Chomsky and Gilbert Achcar came to after debating the question of which Palestinians get to decide on a settlement. See Chomsky and Achcar, Perilous Power: The Middle East and U.S. Foreign Policy, ed. Stephen R. Shalom (Boulder: Paradigm, expanded edition, 2009), pp. 156-57. ↩

- “President Abbas: worldwide Palestinian referendum to approve agreement (where permitted),” Feb. 3, 2011, www.imra.org.il/story.php3?id=50950. ↩

- Harriet Sherwood, “Palestinian leadership matches Israeli PM’s peace deal referendum pledge,” Guardian, 22 July 2013, www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jul/22/palestinian-israeli-referendum-peace-deal/. ↩

- The proposition that Palestinians should “Abandon the two state solution and demand the establishment of one state for Palestinians and Israelis” has been consistently rejected by a two-to-one majority. The attitude toward the two-state settlement is complicated. There seems to be modest support for a two-state settlement (a plurality of Palestinians, from both the West Bank and Gaza, rank as the foremost national priority: “Israeli withdrawal to the 1967 borders and the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip with East Jerusalem as its capital”; small majorities have consistently said they support a two-state settlement generally and the two-state Saudi-backed Arab Peace Plan specifically), yet a majority also say the two state is no longer viable. See the polls of the Palestine Center for Policy and Survey Research, www.pcpsr.org. Ali Abunimah writes: “While polls show that a majority of Palestinians support a two-state solution, their view shifts when they are given a choice only between the cantonization now being imposed and a single state shared with Israeli Jews.” (One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2007, Kindle Edition. Kindle Locations 176-178). This forced choice doesn’t tell us very much. ↩

- Respondents were asked whether they supported, opposed, or were neutral towards the following statement: “A fairer and more viable solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be the creation of a single state in which all citizens have equal rights.”

Zogby, Is Peace Possible? p. 29. ↩

- Ibid., pp. 29, 26. Virginia Tilley offers various caveats about using Palestinian poll data. “This is not to say,” she writes, “that the poll data is wrong” but that we ought to be more cautious in concluding “that Jewish or Palestinian rejection of a one-state solution should be taken as an unyielding edifice.” (Tilley, The One-State Solution {Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005}, pp. 241-42; Tilley, “The Secular Solution,” New Left Review 38, March-April 2006, http://newleftreview.org/II/38/virginia-tilley-the-secular-solution-debating-israel-palestine.) I agree with her that the polls do not show invariant opinions, but this does not contradict my claim that the two-state option currently has the advantage of majority support among Palestinians (and Jews). ↩

- See “The British Anti-Apartheid Movement,” South African History Online, www.sahistory.org.za/topic/british-anti-apartheid-movement?page=2. ↩

- Tom Lodge, Sharpeville: An Apartheid Massacre and its Consequences (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 237. ↩

- “UN and Apartheid from 1946 to Mandela Day,” www.unric.org/en/nelson-mandela-day/26991-un-and-apartheid-from-1946-to-mandela-day-. ↩

- UN Security Council Resolution 418, Nov. 4, 1977. South Africa was able to evade this resolution through various loopholes and by means of a secret agreement with Israel. See Sasha Polakow-Suransky, The Unspoken Alliance: Israel’s Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa (New York: Pantheon, 2010). ↩

- P.L. 99-440, Oct. 2, 1986, www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/

STATUTE-100/pdf/STATUTE-100- Pg1086.pdf. ↩ - Reagan, “Statement on the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act of 1986,” Oct. 2, 1986, www.reagan.utexas.edu/archives/speeches/1986/100286d.htm. ↩

- See the listing of BDS successes at Palestinian BDS National Committee, “The BDS movement at 7: Stronger, more widespread and more effective than ever,” Mondoweiss, July 10, 2012, http://mondoweiss.net/2012/07/the-bds-movement-at-7-stronger-more-widespread-and-more-effective-than-ever.html. The most recent significant victory is EU sanctions against the occupied territories. See Palestinian BDS National Committee, “The era of sanctions against Israel has started’: Official BDS movement statement on new EU regulations against settlements,” Mondoweiss, July 18, 2013, http://mondoweiss.net/2013/07/the-era-of-sanctions-against-israel-has-started-official-bds-movement-statement-on-new-eu-regulations-against-settlements.html; “Guidelines on the eligibility of Israeli entities and their activities in the territories occupied by Israel since June 1967 for grants, prizes and financial instruments funded by the EU from 2014 onwards,” Official Journal of the European Union, vol. 56, 19 July 2013 (2013/C 205/05), pp. 9-11, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2013:205:FULL:EN:PDF. ↩

- Of course Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews can live together. But binational states or any state with two substantial diverse population groups are not easy and require a level of trust and goodwill that cannot be created overnight. Current polls show high levels of racism among Israeli Jews. For example, fewer than half of them are willing to accept Arabs as neighbors and just over half accept integrated schools; more than a quarter would deny Arabs the right to vote in Knesset elections, and almost two thirds would choose the Jewish character of the state if it clashes with its democratic character. See Sammy Smooha, “Still Playing by the Rules: Index of Arab-Jewish Relations in Israel 2012, Findings and Conclusions,” University of Haifa and Israel Democracy Institute, 2013, http://en.idi.org.il/media/2522696/Arab-Jewish-Index-2012-ENG.pdf. ↩

- See the reports of “Who Profits from the Occupation?” a research project of the Coalition of Women for Peace, http://whoprofits.org/reports. ↩

- Tilley (“The Secular Solution”) argues that to think that Zionists would worry that Palestinians would “gain sovereignty over the entire country” is to falsely assume that “identities like ‘Palestinian’ would be permanent features of a one-state solution,” while in fact class and other interests might come to “erode the boundaries of established Jewish and Palestinian ethno-nationalist blocs” and “new social unities” might emerge. I quite agree that new social unities might well emerge, but over time. For a one-state settlement to occur, Zionists would have to agree to give up their sovereignty at the beginning of the process, not years later when new identities have taken hold. I also believe that in a society with economic democracy former bosses will participate in workers’ councils (and their lives will be the better for it), but very few of them will come to this realization while they still hold their power and privilege. ↩

- See, for example, RAND Palestinian State Study Team, Building a Successful Palestinian State. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2007. www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG146-1. ↩

- Some Palestine support activists insist that compensation to refugees has to be paid by Israel and Israel alone, that Israel’s moral obligation cannot be met by contributions from others. This seems an ill-advised position. If someone has been the victim of gross employment discrimination by a supervisor, the financial resources of the supervisor available for punitive damages are far less than that of the corporation, which is why, even if we think that the supervisor bears the main moral onus, we want the corporation to pay damages as well. The United States government isn’t strictly analogous to the corporation (though nor is the analogy totally inappropriate, given Washington’s role in enabling Israel’s many crimes), but it would certainly benefit Palestinians to have governments with deeper pockets than Israel contributing to the refugees’ compensation. That said, it is crucial to any final settlement that Israel acknowledge its responsibility for the Nakba. ↩

- Tilley writes in her case for a one-state solution (One-State Solution, p. 224): “it is almost certain that, as Jews have for so long overwhelmingly dominated the state’s politics and businesses, Jewish ethnic dominance will endure for decades, just as white advantages have persisted in South Africa.” Many Palestinians might find this a not very appealing outcome. ↩

- Financial incentives were used to encourage the establishment of the settlements. Financial incentives could be used to encourage their evacuation. Once some leave, diminishing economies of scale increase the economic burden on those remaining, which would lead to further voluntary movement behind the Green Line. Even many nationalist fanatics might feel an obligation to obey an order to leave from the Israeli government. (See the comment of a settler from Samaria, head of Likud’s student organ: “Many people are wrong in assuming settlers prioritize land over nation. In fact, … the great majority of settlers will obey the decision of the majority.” {Quoted in Gabrielle Rifkind, Pariahs to Pioneers: Could the settler movement be part of the solution and not part of the problem in the resolution of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict? Oxford Research Group, May 2010, p. 15, www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/…/ORG_SettlerReport_0.pdf.}) It’s hard to believe that those settlers who still refused to leave couldn’t be handled by one of the most proficient military forces in the world. ↩

- Abunimah, One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse, Kindle locations 1621-1623 (“A major obstacle to the establishment of a Palestinian state, most settlements could simply remain where they are in a unified country. Palestinians whose land was confiscated for the use of settlements would need to receive full compensation, and the relationship of the settlements to other communities would have to change completely.”); Tilley, One-State Solution, p. 223 (“In a state incorporating such {equal rights} formulas, the Jewish settlements could remain in place.”); Yehouda Shenhav, Beyond the Two-State Solution (Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2012), Kindle location 767 (“in the case of a just agreement, most settlements could remain, although the expansion of these settlements should be halted momentarily.”). ↩

- Some advocates for the Palestinian right of return argue that “The Israeli living in the home of a Palestinian — a home from which the rightful owner fled or was forcibly evicted and to which he is not permitted to return — is a usurper, not an innocent third party. His transfer to another place in Palestine to permit the rightful owner to return, may be an inconvenience but it is not an injustice. Palestinians demand their own return, and not the departure from the country of the alien Jews who have immigrated into the country.” (BADIL, “Rights of return and self determination asserted in all international law,” BADIL Occasional Bulletin No. 23, Dec. 2004, p. 5, www.badil.org/en/documents/category/51-bulletins-briefs?download=584%3Abulletin-23-rights-of-return-and-self-determination-asserted-in-all-international-law.) If this is true for 65-year-old usurpations, where “international law remains ambiguous about how refugees’ and secondary occupants’ rights should be balanced” (Michael Kagan, “Do Israeli Rights Conflict with the Right of Return? Identifying the Possible Arguments,” in Rights in Principle – Rights in Practice: Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions for Palestinian Refugees, ed. Terry Rempel {Bethlehem: BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Dec. 2009}, p. 384, www.badil.org/ar/documents/category/35-publications?download=815:rights-in-principles-rights-in-practice), how much stronger must be the case against allowing usurpations that have occurred in the last 36 years under circumstances where the international law regarding the balancing of rights is much less ambiguous? Shenhav is of course correct that many of the settlers were poor Mizrahim, Russian immigrants, and the ultra-Orthodox, escaping discrimination from dominant elites, but surely they acted under less duress than the survivors of the Holocaust whose immigration to alternative destinations was blocked by Western nations (and sometimes by the Zionist movement: see Yosef Grodzinsky, In the Shadow of the Holocaust {Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 2004}, chap. 4). In any event, the settlers are “happier, healthier and wealthier than other Israelis” according to a 2008 survey. (See Jonathan Cook, “Settlers live better than average Israelis,” The National, 25 Dec. 2008, www.jonathan-cook.net/2008-12-25/settlers-live-better-than-average-israelis/.) Still, in any solution the Israeli state and not individual settlers should bear the brunt of the costs. ↩

- “In short, there is no legal contradiction between the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the right of refugees to return.” BADIL, Rights of return and self determination asserted in all international law,” p. 1. The National Democratic Assembly, the nationalist party of Palestinians in Israel (Balad in Hebrew), calls for the right of return, making Israel a state of its citizens, including minority rights for Palestinians, and two independent states (http://en.idi.org.il/tools-and-data/israeli-elections-and-parties/political-parties/balad/). Even though the secretary general of the party personally supports a one-state settlement (see Jonathan Cook, “‘It’s time for Palestinians in Israel to stand firm against the Bantustan plan of Oslo’: An interview with Awad Abdel Fattah,” Mondoweiss, 12 Nov. 2012, http://mondoweiss.net/2012/11/its-time-for-palestinians-in-israel-to-stand-firm-against-the-bantustan-plan-of-oslo-an-interview-with-awad-abdel-fattah.html), the fact that the platform includes both right of return and two states confirms that there is no necessary contradiction between these. ↩

- Obviously, the number of Palestinians who would return under either scheme is just a guess and there are many problems with the data in any case. But at a minimum we note that about a third of the residents of the Gaza Strip and three quarters of the residents of the West Bank are not refugees (UNRWA, West Bank and Gaza Strip Population Census of 2007, Briefing Report, 2010, www.unrwa.org/userfiles/2010091595334.pdf). So these 2.2 million Palestinians would be part of a one state settlement, but not part of Israel under a two-state settlement with right of return. ↩

- See the argument advanced by Moshe Machover, “Zionist myths: Hebrew versus Jewish identity,” Israeli Occupation Archive, May 17 2013, israeli-occupation.org/2013-05-17/moshe-machover-zionist-myths-hebrew-versus-jewish-identity/. ↩

- The nature of a just binational state is an extremely complex matter, but it must be more than a state that treats each individual equally. It must recognize the collective, national rights of its component national groups, while imposing no penalty on those who aren’t interested in these national identities. Unfortunately, many one-state proposals do not acknowledge the national rights of Israeli Jews. These proposals, in my view, are morally questionable, and needless to say would face even more determined opposition from Israeli Jews than would a single binational state. For some one-state advocates who do explicitly recognize the national rights of Israeli Jews, see Leila Farsakh, “Israel-Palestine: Time for a bi-national state,” The Electronic Intifada, 20 March 2007, http://electronicintifada.net/content/israel-palestine-time-bi-national-state/6821; Abunimah, One Country: A Bold Proposal to End the Israeli-Palestinian Impasse; and Jeff Halper and Itay Epshtain, “In the Name of Justice: Key Issues Around a Single State,” The Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions, Sept. 13, 2012, www.icahd.org/node/423. Tilley argues that “a completely ethnic-blind system would not suffice” (One-State Solution, p. 220), while worrying that inscribing national identities into law would reify the rival identities (“The Secular Solution”). For some group one-state statements that omit any reference to national rights or binationalism, see “The One State Declaration,” Madrid and London, 2007, posted on Electronic Intifada, 29 Nov. 2007, http://electronicintifada.net/content/one-state-declaration/793; and “Declaration of The Movement for One Democratic State in Palestine,” Dallas, Texas, 2010, www.onedemocraticstate.org/Declaration-Full-Text.aspx. So long as a single state is a future aspiration, its precise details don’t need to be worked out at this time, but the lack of clarity on fundamental aspects of a just one-state solution makes current advocacy on its behalf that much more difficult. ↩

- Note also that a Palestinian state with many refugees living in it would provide a good base for peacefully pursuing the right of return, something that is very difficult for the refugees to do while living in camps in Lebanon. ↩

- A “Jewish” state is clearly more objectionable than a Palestinian state, given that Jews are an ethnicity and a religion. ↩

- There were various binational proposals at the time, differing most significantly on the immigration question and how to handle national communities of different sizes. See on Ichud (Ihud), Paul R. Mendes-Flohr, ed., A Land of Two People’s: Martin Buber on Jews and Arabs (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), esp. pp. 148-49; on the Arab League proposal, Neil Caplan, Futile Diplomacy, vol. 2, Arab-Zionist Negotiations and the End of the Mandate (London: Frank Cass, 1986), esp. pp. 272-74; and on the minority report of the UN Special Committee on Palestine, see United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP), Report to the General Assembly, Official Records of the Second Session of the General Assembly, Supplement No. 11, Volume 1, A/364, Lake Success, New York, 3 September 1947, http://unispal.un.org/…/…FA2DE563852568D3006E10F3; UN, Department of Public Information, Yearbook of the United Nations, 1947-48, 1949.I.13 (New York: 31 Dec. 1948), chap. 9: The Question of Palestine, http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/…/…f852562bd007002d2. Ichud opposed any limitations on Jewish immigration (“Ichud Party Issues Declaration on Immigration and Zionist Discipline,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Oct. 11, 1942, www.jta.org/1942/10/11/archive/ichud-party-issues-declaration-on-immigration-and-zionist-discipline#ixzz2bDzPlSji), while the binational proposal of the Arab states insisted that Jews never exceed one third of the population, and that Jewish displaced persons then in Europe be absorbed by member states “in proportion to their area, economic resources, per capita income, population and other relevant factors.” UNSCOP’s minority plan called for a federal arrangement, but with immigration to be controlled by the center. ↩

- As Pakistan’s U.N. delegate put it, “If it is unfair that 33 percent of the population of Palestine {the Jews in the proposed unitary state} should be subject to 67 percent of the population, is it less unfair that 46 percent of the population {the Arabs in the proposed Jewish state} should be subject to 54 percent?” Quoted in Walid Khalidi, “Revisiting the UNGA Partition Resolution,” Journal of Palestine Studies, vol. 27, no. 1 (Autumn, 1997), p. 11. ↩

- For example, a recent statement by Jews for Palestinian Right of Return (Jan. 1, 2013, http://jfpror.wordpress.com) approvingly quotes Palestinian journalist-activist Maath Musleh as saying: “If you think that {return} is not possible, then you are really not in solidarity with the Palestinian cause.” ↩

- Note that the apartheid regime had no two-state option. Once apartheid became untenable, they had no choice but to accept majority rule. In Israel’s case, Zionism has several options before surrendering to the one-state arrangement. Israel could for example annex the West Bank and give voting rights to the Palestinians there. Because Gaza would not be part of the state, Jews would remain a majority and could use their majority status to block any Palestinian return. Most remaining international pressure on Israel would likely be lifted. ↩

- Some “one-staters” argue that, yes, a one-state settlement has only a one-in-a-million chance of realization, but a two-state settlement has only a two-in-a-million chance, so since both are so unlikely we might as well push for our preferred choice. I have two problems with this approach, apart from believing the relative odds to be rather different. First, if we’re going to be expressing preferences detached from any realistic chance of success, then why stop at a one state; we might as well go for broke and talk of a socialist federation in the whole Middle East, or whatever our ideal happens to be. Second, as activists there are many causes we support in the abstract, but we don’t have the time, energy, or resources to pursue them all. We make choices based on our personal inclinations, but also on where we judge that our efforts will get the most return. If I believed there was only a one-in-a-million chance of success from pursuing a particular cause, I probably would take up some other cause. ↩

- E.g., David Poort, “The threat of a one-state solution,” Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011, www.aljazeera.com/palestinepap…/…/201112612953672648.html. ↩

- See the discussion in Hussein Ibish, “What’s Wrong with the One-State Agenda? Why Ending the Occupation and Peace with Israel is Still the Palestinian National Goal,” American Taskforce on Palestine, 2009, www.americantaskforce.org/what’s_wrong_onestate…html, pp. 43-45. ↩

- Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin: Ratification of the Israel-Palestinian Interim Agreement, The Knesset, Oct. 5, 1995, www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/mfa-archive/1995/pages/pm…agree.aspx. ↩

- Ibish, “What’s Wrong with the One-State Agenda,” p. 12, citing an April 17, 2009, twitter feed from Ali Abunimah. ↩

- See the comments of Toufic Haddad, a one-state advocate, in “The ‘End of the Two-State Solution’ Spells Apartheid and Ethnic Cleansing, not Binationalism and Peace,” Jadaliyya, Nov. 17, 2012, www.jadaliyya.com/pages/index/8460/the-%E2%80%9Cend-of-the-two-state-solution%E2%80%9D-spells-aparthe. ↩

- Peter Beinart, “To Save Israel, Boycott the Settlements,” New York Times, March 19, 2012 (online March 18, www.nytimes.com/2012/03/19/opinion/to-save-israel-boycott-the-settlements.html). ↩

- Some have suggested a “gradual binationalism” that begins with two independent states, but moves as conditions improve to a binational arrangement. Various schemes currently being considered for Jerusalem might form the basis for such an approach. See Oren Yiftachel, Ethnocracy: Land and Identity Politics in Israel/Palestine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), chap. 12, www.geog.bgu.ac.il/members/yiftachel/books/chp_12_print.pdf; Michael Dumper, “‘Two State Plus’: Jerusalem and the Binationalism Debate,” Jerusalem Quarterly, Autumn 2009, 39, www.jerusalemquarterly.org/ViewArticle.aspx?id=313. ↩