By Yotam Feldman and Uri Blau, Haaretz – 13 Aug 2009

English: www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1107419.html

Hebrew: www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/spages/1105703.html

IOA Editor: The Hebrew version of this article was published on 7 Aug 2009. The original header read: “200 West Bank villages are not connected to a pipe. That’s how Israel is drying out the residents of the PA”

Hirbet Attawna well: producing 8 - 10 liters per resident per day

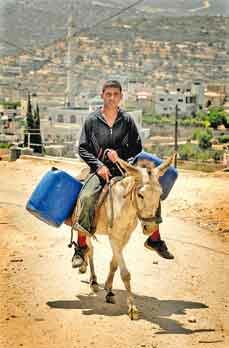

Many of the villagers of Qarawat Bani Zeid are obsessed with water – chiefly, its absence. From their home, Jabar and Sabri Arar order a container of the precious fluid for a neighbor who can’t afford to have it delivered from a distant village. “Sabri and I are communists,” Jabar explains. “We cannot drink while our neighbor goes dry.” Mufid Hamadan, 48, brings four plastic jugs of water from a nearby spring by donkey. Trucks bring water from the neighboring villages of Burkin and Kafr al-Dik – NIS 300 for a container of eight cubic meters, enough for a family’s minimal needs for three weeks.

Qarawat Bani Zeid - water transport

Village council members say that for the past five years the water supply to the village stops almost completely in June, for the duration of the summer. The lowest houses get water once every few days, but the faucets of the higher ones are dry for the entire summer. The councillors note that this year – the third drought year in succession – the water outages started earlier.

As early as April the village was getting water only once a week, and only enough for 15 percent of the residents. By June it had gone down to just once every ten days, with sufficient water for only 5 percent of the villagers.

The Israeli water company Mekorot, which supplies the water to villages in the area, said it is not aware of the problem. Nevertheless, all the villagers keep full pails of water at home and have gone to great lengths to reduce their water use. They have stopped farming and raising livestock – essential sources of income – and are showering much less, even at the height of the summer. And the floor-washing that traditionally involves copious amounts of water has been reduced to a matter of a few cups’-worth.

The water shortage here is particularly surprising in light of Qarawat Bani Zeid’s location: 17 kilometers east of the Israeli city of Rosh Ha’ayin and on top of the Western Mountain aquifer, an abundant reservoir of groundwater shared by Israel and the Palestinian Authority.

The source of the reservoir is rainwater that falls in the areas of the Palestinian Authority and percolates into the ground. The water collects on both sides of the Green Line. To date, the Israeli Water Authority has vetoed pumping by Palestinians from the reservoir – which stretches between the hills of the West Bank and the Rosh Ha’ayin area in the west – beyond the tiny amount they pump from wells predating the Oslo Accords.

The division of the water in the shared Israeli-Palestinian reservoirs is far from equal. Under Oslo, Israel has the right to pump 443 million cubic meters a year, while the Palestinians are permitted to pump just 64 million cubic meters annually.

All told, the water from shared reservoirs makes up about one third of the fresh water consumed in Israel. In other words, one of every three drops of water streaming from faucets in Israel comes from rain that fell in the West Bank.

“We live above an underground Lake Kinneret, a sea of water, but we have nothing to drink,” Jabar Arar says. “It seems as if it’s Israeli policy to strangle those who live here.” Arar and others in the village have begun protesting the unjust water distribution. Earlier this month they joined forces with Israeli leftist groups to arrange a water convoy to the village. Other residents in the area, however, are less patient with this unfair distribution of resources.

“It’s very simple and straightforward,” says a man from a nearby village. “Everyone can see the differences between the villages here and the [Jewish] settlements. From here you can see the green trees in Halamish, in contrast to the dried-out trees in our village; you can see those who have a water infrastructure, while we have to pay for containers. If things continue like this we will have no choice but to cut the main pipes bringing water to us and to the settlers, so they will feel what we are feeling now. If we are being told that there is a water shortage, then let there be a shortage for everyone, not just us.”

The situation of Qarawat Bani Zeid and surrounding villages is not exceptional for the West Bank. Many Palestinian communities experience water shortages and 200 West Bank villages are not even connected to the water grid. Even Ramallah, the seat of Palestinian government, which has been enjoying a relative boom and is at the top of the PA’s order of priorities, has running water only two days a week. (Most people are not overly affected by this, thanks to the rooftop water tanks they use when the faucets go dry.)

Kafr Susia well

The villages of the Aqraba area, east of Nablus, have no running water at all. They get their water from two filling stations in the villages of Hawara and Qusra.

At midday on Saturday Ahmed Hassan, 18, waits for an eight-cubic-meter container to slowly fill. This station, in Qusra, serves about 3,000 locals. A group of teens waits patiently in line for his container to fill – a matter of several hours. Mekorot has fitted a flow reducer to the pipe. It takes an entire day for the teens to fill just two containers. Everyone keeps a list of those who wait in line, after signing up a few days before. The amount available is far from enough for all the villagers, and the unlucky must pay more to have water brought in from farther away.

Only the executor

Mekorot says it is only the executor. “The allocation of water to the Palestinian Authority is decided by the Israeli Water Authority in accordance with diplomatic agreements. Mekorot operates in accordance with the instructions of the water authority and transfers amounts of water accordingly.” Mekorot says it “supplies the water to the Palestinian Water Authority but is not responsible for the internal distribution in the communities of the West Bank; the body responsible for that is the Palestinian Water Authority.”

Mekorot maintains that the supply of water to Qusra has not been affected: “Our measurements show that in Qusra 650 cubic meters of water per day were supplied in July, meaning about 30 cubic meters an hour. The reducer is a standard means used by companies all over the world to regulate the water among the different users and prevent water loss. This is the case with both Israeli consumers and the PA.”

Jawdat Bani Jabar is head of the Aqraba council, which oversees neighboring villages as well. He says that in the summer there are disruptions to the water supply and sometimes no water at all during the day. At the same time, he says the water supply is expected to improve significantly soon, once a second well and two water reservoirs in the nearby village of Rujeib become operational.

“Regarding humanitarian matters Shaddad Attili [head of the Palestinian Water Authority] can call me,” the head of the Israeli Water Authority, Prof. Uri Shani, says. “There is great openness on the humanitarian side.” To which Dr. Attili replies: “If I were to call Shani with every humanitarian problem his phone would be ringing 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. There are humanitarian cases throughout the West Bank.”

According to Mohammed Jaas, who until early this year was general director of the West Bank Water Department, complaints about water shortages among Palestinian villages without central water distribution receive a particularly slow response.

“Early last year we gave the Israelis a list of areas with water shortages. It took until the end of the summer to deal with the list, and they said they would take it into account for 2009. Carlos [Percia, chief engineer for Mekorot’s central district] told us there is no water this year and that we’ll talk about it next year.”

In April the Palestinians met with representatives of the Israeli Water Authority at Civil Administration headquarters in Beit El. Jaas: “The meeting started at a quarter to three and at 3:20 we were told, ‘If you don’t leave, the soldiers will close the gate and you won’t be able to leave.’ So we ended the discussion.” The Israelis, he adds, postponed a meeting scheduled for June 24. Percia says in response: “Mohammed knows that the authority does not rest with Mekorot or with me, but depends on what is stipulated in the agreements.”

An internal Civil Administration document reported that as of last year dozens of West Bank villages depend on water tankers for their needs. In the Jenin sector, for example, 24 of 78 communities are listed as receiving all their water by tanker. In the Tul Karm area it is three of 35 communities, in the Qalqilyah vicinity that number is 5 of 56. In the Nablus region, 21 of 58 communities depend on water tankers. Two of 40 Bethlehem-area communities get water that is trucked in, while in the Hebron area it is 7 of 82 communities and near Jericho, 1 out of 21.

According to a World Bank report from April, around one quarter of West Bank Palestinians in communities with running water receive less than 50 liters a day – half of what they need. Some people get less than 15 liters a day. (A quick shower uses 50 liters of water, and it takes nine liters to flush the toilet).

The Israeli Water Authority vehemently disputes the World Bank data and proposes far more optimistic numbers, but it does not deny that there is a severe water shortage in the West Bank. The authority emphasizes that the water crunch is being felt in Israel, too, and that its primary cause is climatic conditions. However, others maintain that the water crisis, like the unequal distribution of water, is part of a systematic Israeli policy.

According to Gidon Bromberg, the executive director of EcoPeace/Friends of the Earth Middle East, which has offices in Israel, Palestine and Jordan, the Israeli attitude is that all the water is ours and that we do not have to share it with anyone. He reached this conclusion in part from a conversation with water authority head, Shani. In response, Shani says that the water shortage in the West Bank pains him but that the PA is to blame. “If the Palestinians were to distribute the water with an efficiency that approaches ours they would be in good shape. But more than a third of their supply is lost in the pipeline, and their agriculture uses fresh water, not treated wastewater.”

Still, they receive a relatively small amount. Why not share the water equally?

Shani: “Israel sticks meticulously to the agreements, and I can say with full authority that where water is concerned the Palestinians are not subject to much discrimination. Most of the problems are due to inefficiency. The definition of what’s equal is difficult and complicated, and if you consider all the parameters you’ll see the distribution is equal.”

A bad agreement

There are three subterranean water reservoirs in the West Bank. Two of them – in the west and in the northeast – straddle the Green Line and so are common to both Israel and the Palestinians. The eastern aquifer lies entirely in the West Bank. The waters of the Jordan River are also shared, at least in theory, though in practice Israel blocks the river’s outlet from Lake Kinneret and does not give the Palestinians access to the little water that flows in the river, the west bank of which is a closed military zone.

Ahead of signing of the Oslo Accords, the Israelis and Palestinians tried to map the water needs of the Palestinian economy and to distribute the common water resources accordingly. Both the officials in charge of the Palestinian water supply and international experts who are engaged in dividing the resources now agree that the arrangement was bad for the Palestinians.

According to one PA source the Palestinian negotiators themselves have admitted in retrospect that the agreement was detrimental to their interests. Under the agreement, the Palestinians are not permitted to pump additional water from the joint Israel-PA aquifers. The accord stipulates that they must provide for all their water needs from the eastern aquifer, the one located entirely in the West Bank. The framers of the agreement estimated that another 70 to 80 million cubic meters a year could be pumped from that source. Even though the time period of the interim agreements ended in 2000 and the Palestinian population has grown since then, the water amounts have not been changed.

In the talks that began in the summer of 1995 the delegations were unable to agree on even one article of the agreement. The heart of the dispute was the Palestinians’ demand that Israel recognize their “water rights.” The head of the Israeli team, Noah Kinarti, a confidant of Yitzhak Rabin, refused to accept this. Finally, agreement was reached in general terms on water rights, but when discussions on the details began, Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat decided the delay was liable to jeopardize the entire agreement. He dismissed the Palestinian delegation and left only his confidant, Nabil Sharif, at the negotiating table.

Sharif, a former Palestine Liberation Organization ambassador to Colombia, knew nothing about the water situation and not much more about the general state of affairs in the West Bank. His opposite number was a well-informed Israeli team equipped with data, charts and plans to divide the water between the two sides. One of the Palestinian water experts told the British researcher Jan Selby (who quotes him in his 2003 book “Water, Power and Politics in the Middle East”) that the Palestinian team did not even read the water agreement before signing it – otherwise, it would not have signed. The technical experts did not sign any document, the Palestinian source told Selby; only politicians signed, and the result speaks for itself.

In a conversation with Haaretz, Kinarti, who is now chief adviser to Israeli Water Authority head Shani, repeatedly describes the Palestinians as liars. He says that for the past 15 years the Palestinians “have been lying about the data all the time and have been engaged solely in politicking.” He says they “travel the world spreading lies and falsifications about the amount of water, about everything.”

The Palestinians claim to suffer from an acute water shortage.

“Liars,” Kinarti says. “They have enough water to drink… There are water tankers in Amman and Damascus, too. That’s how they do things. In the interim agreement they were given at least 70 to 80 million cubic meters of water [a year] from the eastern aquifer. They did nothing. They want us to bring them water and to live at our expense. They want Lake Kinneret, the coastal plain, what don’t they want?… We let them dig [wells] in the eastern aquifer; there is water there, so let them dig, God damn it. Why aren’t they digging? For no reason, because it’s easier to cry. Do they care about their nation? They want to be miserable.”

What do they get out of it?

“I don’t know. They steal half the money [from the donor countries], maybe less today but they used to steal the money.”

In a previously unpublished 1998 interview to Selby, Kinarti argues that the Palestinians do not need as much water as the Israelis. “It’s a kind of culture… It’s a fact… Sometimes we were good, good people, and we brought, for example, a pipe with water to an Arab village here in the West Bank. Before this pipe [existed], they had to go to the fountain, the women with a jar on their head, [to] get the water… When we brought this water, so we put a small pipe into every yard, and you think they can go ahead and use it, put in toilets with running water and showers and things. No, they put the small pipe into the barrel [in the yard] and served the water from that.”

Good atmosphere, few results

The inequality of water distribution between Israelis and Palestinians is particularly flagrant in the Jordan Rift Valley. Driving through the valley with Fathi Hadirath, a director of the Palestinian development agency Ma’an, we see large, fenced-in pools that the Jewish settlers use for irrigation. According to data collected by B’Tselem, the Rift Valley settlers, who engage in water-rich agriculture, are allocated more than 1,000 liters of water per person a day, all from the eastern aquifer, which lies entirely in the West Bank and to which by international law Israel has no rights.

Hadirath, who lives in his hometown of Bardala, in the northern Jordan Valley parks his Jeep near a community of 350 Bedouin near the village of Jiftlik. The heat, which can reach 48 degrees Celsius, slams into us. The walls of the houses are too hot to touch for more than a couple of seconds. In his home, Abd al-Rahman Samirath turns on the faucets. Not a drop of water comes out. The family has running water only once a week. The rest of the time it must rely on expensive, trucked-in water.

Samirath’s family, like all the families in this arid region, save every drop of water they can. They have only 500 liters of water a day for the needs of seven people, plus their herd of more than 20 sheep. The money they spend on water – NIS 80 for a three-cubic-meter container – comprises more than 30 percent of their total monthly income.

Hadirath, who was head of the Bardala local council from 1995 to 2006, describes the Israeli policy as “indirect ethnic cleansing” aimed at removing the inhabitants of Area C [the area under exclusive Israeli control under the Oslo Accords] in the Jordan Rift Valley. “They allow the residents of Jericho and five villages that receive a reasonable supply to develop water sources, and are trying to expel the others by stopping the flow of water.” This policy, Hadirath says, has succeeded in many places. The difficulty of obtaining water, and its exorbitant price, is prompting many families to leave the Jiftlik area, especially in the summer, in favor of Jericho and other villages. Some families return home in the winter, but others do not.

“There is nothing I can say to them,” Hadirath explains. “I can try to help with getting water containers or persuade international organizations to give them containers for free, but I can’t tell them not to leave.”

Since the signing of the Oslo Accords, a joint water committee, currently headed by Shani and Attili on the Israeli and Palestinian sides, respectively, has been responsible for authorizing new water projects for the Palestinians and the settlers.

At the start of the Oslo process the committee met every few months at Neve Ilan or Yad Hashmona outside Jerusalem, or at Mekorot offices in Ramle. Now they meet around once a year.

Speaking in Ramallah, Jaas, the former head of the West Bank Water Department, notes that the atmosphere in the meetings is generally good but that they tend to be quite short relative to the long list of projects. “The meeting is supposed to start at 10,” he relates, “but usually we have coffee at the beginning and start late. Lunch is served around 1, and then one of the Israeli representatives has to go back to Mekorot, another to the university, and the meeting breaks up.”

The atmosphere may be positive, but the committee can boast of few achievements toward developing Palestinian water resources. According to the World Bank report, the Palestinians have access to only 20 percent of the water reservoirs they share with Israel. Moreover, despite Palestinian population growth, the overall amount of water at the Palestinians’ disposal fell from 118 million cubic meters in 1995 to 113 million cubic meters in 2007. The number of wells available to the Palestinians declined from 774 in 1967 to 328 in 2006. According to the Palestinian Water Authority, all the new pumping since Oslo has produced only 20.3 million cubic meters of water a year, instead of the promised 70-80 million cubic meters. (Some estimates are even lower). Israel has offset part of this disparity by increasing the amount of water that Mekorot sells to the PA from 28.6 million cubic meters a year – its obligation under Oslo – to 50 million cubic meters. As a result the Palestinians are now even more dependent on Israel for water.

Shared secrets

The minutes from the meetings of the joint water committee and of its technical subcommittee are secret, and the public is unaware of much of the political pressures exerted within them. Indeed, the involvement of PA officials in authorizing the settlements’ water plans is an extremely sensitive political issue, so the Palestinians, too, are loath to reveal the contents of the discussions.

Jaas, who has attended all the committee meetings in recent years, says they are a far cry from the idyllic cooperation envisioned by Oslo. “It was said that the agreement has to be implemented with the goodwill of both sides, and goodwill is very important.” But, he says after two years the goodwill of the Israeli committee members ran out. “They still think of this land as being occupied and of the water as belonging to them,” Jaas says.

This attitude is reflected in an unwillingness to authorize Palestinian projects and in the form of obstacles heaped up by Israel. After Hamas rose to power in 2006, the committee did not meet for a year and a half; the Palestinian projects piled up even as the supply of water in the West Bank continued to decline. The Palestinians, too, canceled meetings at the start of the intifada, when the Israel Defense Forces entered Palestinian cities, and also during Operation Cast Lead in the Gaza Strip.

“Generally, four Palestinian projects are discussed in each meeting,” Jaas says, “and then the Israelis say, ‘Now we will stop and move to our projects,’ and present a plan relating to the water supply in the settlements. If we do not approve an Israeli project it’s a shock. They don’t give something for nothing. They say, ‘Do you think we will discuss only your projects?’ If we do not give our approval the meeting ends, the minutes are not signed and we have to re-present even the projects that were already authorized.”

In three cases, Jaas relates, the Israelis submitted unusually large projects in the settlements. Apprehensive about authorizing them, he said he would have to consult with the Palestinian Water Authority. Even in those cases, he says, the Israelis stopped the meeting and suspended authorization of the Palestinian projects. According to Shani, this is no longer how things are done; his predecessor, Shimon Tal, says he had no recollection of this.

Attili says the the Israeli committee members refuse to discuss Palestinian requests to dig wells in the shared aquifers that would provide for the minimal needs of the Palestinians. The Palestinian Water Authority now believes the amount of water that can be extracted from the eastern aquifer is closer to 40 million cubic meters per year, only half the Palestinian needs as estimated by Oslo. In its 13 years the joint committee has authorized the drilling of 36 wells by the Palestinians, of which only 18 are functioning. (Two await Civil Administration approval, while the remaining 16 are not operational for various reasons.) The committee has not authorized 102 requests to rehabilitate wells for agricultural use. According to the World Bank, of projects worth a total of $121 million the committee authorized projects worth half that amount in 2001-2008.

In a response to the World Bank report the Israeli Water Authority stated that 70 wells had been approved, but the authority declined to give Haaretz the list even after repeated requests. Shani says he knows nothing about Palestinian requests to rehabilitate agricultural wells.

Stronger than security

Like the Jordan Rift Valley, the southern Hebron Hills also show a significant disparity between the supply of water to the cities and to Area C, in what appears to be an attempt to pressure the residents there to move to the cities. Thus, the 23,000 people of Bani Naim receive an average of 70 liters of water a day per person – 20 liters more than the PA average but 30 liters below the minimum for domestic consumption according to the World Bank. One result is that people have reduced the crops needing irrigation.

A drive through the area around Khirbet a-Tauna shows clearly the settlers’ crops, such as the lush vineyards and the plant nurseries of Susya. The situation in Khirbet a-Tauna is very different. The villagers, who have been waging a years-long battle against the army and the Civil Administration for the right to continue living here, use a shallow well for their immediate domestic needs. Local children and teenagers fill jerricans, in amounts that average out to eight to 10 liters per person a day. Those who can afford it bring in water tankers from the town of Yatta, at NIS 30 per cubic meter. There is also a water hole for common needs, such as the school and the clinic, and for those for whom the shortage causes particular hardship.

The head of the a-Tauna council, Sabr al-Harini, says the Civil Administration is trying to force out residents by degrading their water supply. Five months ago, for example, the Israeli authorities issued a demolition order for the water hole. Harini says that in 2004 he asked the Civil Administration to connect the village to the water infrastructure but has yet to receive a reply. In the meantime, the most conspicuous vehicles on the roads are water tankers operated by international nongovernmental organizations. Many families get most of their household water from these tankers.

Prof. Joseph “Yoske” Morin, a retired soil expert who takes human rights activists on tours of the southern Hebron Hills, notes that on at least two occasions he witnessed Mekorot employees harassing Palestinians in the area. On June 24, 2008, Morin said he observed a Mekorot employee shutting off the main water pump to Yatta. When asked why, he said that two nearby Jewish settlements were not getting water.

“The company’s water systems are daily targets of sabotage by Palestinians, although the pipes serve a Jewish and Palestinian population jointly. This sabotage, together with a widespread phenomenon of theft of water from the pipes by Palestinians, is seriously affecting the reliability of the water supply to Jews and Palestinians alike,” Mekorot said in a statement. The company said the pipeline to Yatta and the vicinity are similarly affected. “To repair the breakdowns on the pipeline the connection to Yatta and to a few Jewish settlements was temporarily shut down, and this was coordinated in advance,” the water company said.

The lack of water infrastructure in Palestinian-controlled areas throughout the West Bank is only partially connected to the Oslo Accords and the joint water committee. It is also the result of Israel’s Civil Administration policy, which must approve all projects in Area C even after they have been approved by the joint committee. According to Israeli, Palestinian and international sources, Civil Administration bureaucrats are in no rush to upgrade the water supply to the residents of these areas.

A former very senior officer in the coordinator of government policy’s unit in the territories says, “Overall, we see to it that the settlers will have water in abundance and the Palestinians will not. The quantities per person calculated for the settlers are twice as large as those for the Palestinians. This is embarrassing and disgraceful, and we have already heard racist quips about whether the Arabs shower or not and how much water they need or don’t need. This shameful state of affairs leads to huge water thefts and illegal drilling.”

According to this officer, the Civil Administration bureaucracy applies a particularly tough policy toward the Palestinians. So potent is the apparatus, the officer says, that even senior personnel in the unit are unable to step up the authorization of permits for the development of Palestinian water sources. According to the officer, this approach is most prominently embodied in the person of Shlomo Moskowitz, the Civil Administration’s planning bureau director. “Moskowitz badgers the Palestinians and makes demands that they cannot fulfill,” the officer says. “He is a person with a skullcap who does not believe in the agreements, in handing over territories or in Palestinian independence.” Senior figures in the Civil Administration say that Moskowitz is simply a meticulous bureaucrat and is similarly strict with the settlers. But in at least one case this was not so. Three years ago, Haaretz reported that Moskowitz, an Interior Ministry employee who was “on loan” to the Civil Administration, provided the settlers of Modi’in Illit with building permits contrary to the law and explained that he did so because of the need “to create facts on the ground.” The water authority’s response to the World Bank report emphasizes the foot-dragging by the Palestinians in building water treatment facilities, as a result of which the groundwater is being contaminated and fresh water is being lost.

While the Palestinians are not rushing to build purification plants, they say that part of the problem is the Civil Administration’s unreasonable demands. The administration, for example, insists on an extremely high effluent standard that exceeds those of Western Europe as well of Israeli treatment facilities.

The Palestinian Water Authority says this demand led the Europeans to lose interest in the projects. The Civil Administration agreed to reduce its standards but continued to insist on the submission of a phased plan, with this standard as the final target. The head of the infrastructures unit in the Civil Administration, Lt. Col. Amnon Cohen, notes that this is a goal for the future and need not affect current implementation.

The Civil Administration is working efficiently to advance the Palestinian projects, Cohen says. “There is no policy or intention to fudge, mess up or delay,” he states. “We are not doing anything negative to the Palestinian projects.” As proof, he says, of 39 Area C projects authorized by the joint committee since 2001, the Civil Administration has approved 21, four are being worked on by staffers and 11 have not yet been submitted.

An examination of the administration’s own figures tells a different story. Eleven of the 21 approved projects waited more than a year for the administration’s go-ahead. In some cases it is difficult to understand the cause of the delay. In one case, the Palestinians wanted to dig a well in the Hizma area, north of Jerusalem. The Civil Administration rejected four proposed sites, forcing the Palestinians to wait until the next meeting of the joint committee to authorize new sites. The first request, by the way, was submitted in October 2000 and has not yet been approved.